CHAPTER 7

Agriculture

CLEARING THE LAND

The pioneers that settled in the Formosa area

and the Townships of Carrick and Culross between the years 1852 and 1862 lead a life filled with innumerable hardships. Before those early

farmers could get down to practising their

occupation, the land had to be prepared for farming. This area was a dense forest populated with virgin

timber, great in size, but of no value

except for lumber to be used in building construction. Hemlock and pine were the most weather-resistant

wood, while cedar was used for roofing

material, such as shingles. These were split by hand before shingle mills were brought into the area from

the older settlements.

The task of building shelter was foremost in

the minds of the early settlers. Once

a bit of land was cleared and the brush burned, the main tool of the pioneer

was sharpened, and again this axe was busy. The houses and barns were all built from logs flattened on two sides and notched at the ends to hook together to be held

securely. Between the logs the spaces

were then plastered with a piaster made out of lime,

water and sand, called

chinking.

The lime was burnt out of limestone found on

some of the farms. The stones were placed in a kiln with an oven made of hard

stone built underneath and then

fired with a great heat supplied by mostly heavy cord length or limb wood. This firing took three

or four days, until the limestone was

burned to a powder. It was then left for a few days to cool before it could be handled. Now with a home

and a few acres of cleared land the

settlers were ready to seriously practice the art of farming.

LIVESTOCK

The most important stock to the farmer were

his animals that provided

power. At first the slow, patient and enduring oxen

were used as the beasts of

burden, but gradually, as the land was cleared, more and more horses came into use. About the year

1900, Lawrence Montag sold the last yoke

of oxen in the area. The horse then became the main source of farm power.

In those early years, each farmer had a cow

for milking and a few chickens. In

the winter, the cattle were let graze in the bush in hope they would find enough greens to survive.

In the 1860's, with the advent of grain

crops, farmers began raising many more

animals. The fat cattle overseas market was soon opened with the most practical weight being twelve hundred

to sixteen hundred pounds. The breeds

desired for this trade were mostly Durham or Shorthorn Hereford and Aberdeen Angus. The dairy breeds

at this stage were not very general

as the cheese and cream factories operated only in the summer. The odd Jersey or Guernsey or Swiss

mixed with a beef strain was considered

a good dual strain.

By the end of

the 1800's and the beginning of the 1900's hogs were just becoming popular. Drovers at

that time had a delivery date each week, varying in the different areas. The

livestock was shipped by rail mostly to Toronto. With the invention of cars and

trucks, trucks became the means of transportation to get the stock out to market. The trailer began to be used behind the car, to

go to the mill or market, and cattle were never driven to market any more.

BEEFRINGS

Some animals were needed for home consumption as most people raised their own meat.

In the village there were little

barns built on the corner of a number of lots and a cow

or two were usually kept to supply milk for the

family. With the surplus milk and scraps a few pigs were fed during the summer,

fattened and slaughtered for food in the fall.

Grain and hay were easily obtained

from the farmers, often in exchange for work

performed at harvest time or with building projects.

In the late 1890's beef rings came

into existence and were quite common as

there was no refrigeration. Sixteen members belonged to each ring and each person supplied one beast

per summer_ A two-year-old heifer,

dressing around four hundred pounds was the preferred choice. A butcher was chosen

and it was his duty to cut up and divide the meat. Each family received a different portion each

week, weights were recorded and in the

end each member had received a whole animal.

Slaughtering usually took place on

Friday evening. The beef hung over night and between four and six a.m. the

cutting and dividing was done. Each

shareholder was expected to pick up his share of meat between six and seven a.m. the hide, tallow and

fat went to the owner of the beast. In the

fall of the year a meeting was held at the home of the butcher to tally all the weights of meat

delivered and anyone who received any extra meat

paid for it to reimburse those that were short.

These beef rings continued until

between the 1940's and 50's. Some of the known

butchers of the Formosa area were Alphonse Zettel,

Frank Schaefer, John Bohnert,

Herb Benninger, Albert Schaefer, Jos Stroeder, Jos Weber, and Mathew Weiler.

DAIRY

As farms became more established in

the 1870's and 80's, dairy operations

began to blossom. Because there were no milking machines, and the cows had to be milked by hand, and

because milking was a real chore at the

end of a long day in the fields, only ten or twelve cows comprised an average dairy herd.

Teeswater Creamery established in

1875 was the first creamery in Ontario and

the second in Canada. Some years later Formosa opened a creamery which operated

in the summer months only, for about ten years.

This 'Eskdale Creamery'

manufactured butter for export. One of the butter makers was Edward Kuntz,

father of Herbert. In 1896 an uninsured butter shipment destined for England was lost at

sea causing the Formosa Eskdale Creamery to shut its doors.

Milk collected from the cows was placed in

cans by the farmers, then left to cool

in a fresh spring water box or in a water box in the pump house. The cream was either skimmed off the

top or the milk was run off from a tap at the bottom of the can.

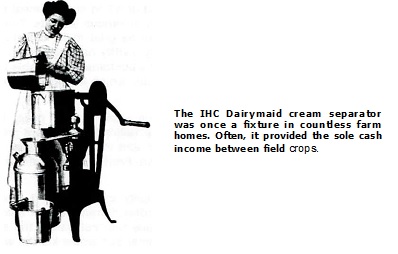

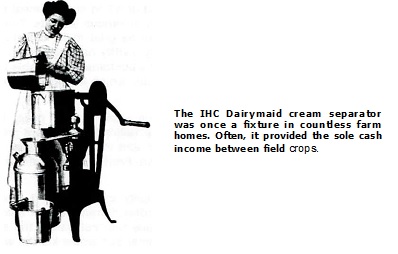

Cream separators began to be used about 1910.

The cream was gathered with a horse

drawn wagon supporting a large tank. To test the cream a ladle of cream was taken from the can and put

in test tubes carried on top of the tank and then the rest of the cream was

poured into the tank.

In the early 1920's Thompson

Bros. purchased the Teeswater Creamery and

with the introduction of motor trucks most of the cream was gathered in that

fashion. Winter months still saw the horses and sleds hauling the cream to town as late as the 1940's as the roads were not snow plowed.

Hydro was brought in on the main

line in the early 1930's while many of the

concessions did not enjoy this convenience until 1948. As hydro was introduced so was the milking machine,

which enabled farmers to increase their

dairy herds.

In the pioneer years, farmers

stocked a variety of animals but in these modern

times many farmers specialize in dairy, beef, poultry, hogs or perhaps the raising of cash crops.

CROPS

The earliest pioneers first

planted potatoes to sustain life while they were clearing

the land. Then a little grain was planted and gradually the farmer could

produce enough so that some could even be sold.

The first wheat grown was spring wheat, which

is a harder variety than the

present winter wheat. Winter wheat has better milling qualities for bread flour. The two wheats were sometimes

mixed and used for pastry flour.

A little rye was also planted. This

grain, similar to wheat, was also ground and used for the making of a not too

tasty deep brown rye bread.

Barley was grown to some extent

for malting purposes while oats was a good

nourishing horse feed, that could also be used as a breakfast food for the humans. The oats were crushed or

rolled and the meal separated from the

hulls, then packaged in bags of various weights. The work of grinding grains

was done in mills known as grist mills, or oat-rolling mills, which were usually built beside a very

swiftly running stream so as to operate the

mill on cheap waterpower. If a customer was unable to

pay for the processing services, he would leave

toll, which was a portion of the grist.

A very early and common cash crop was that of peas, being

processed as food for humans. By the early

1900's farmers were growing as well, a

variety of root crops, e.g. turnips and mangolds. Beans, some buckwheat and a little corn were also grown.

Fruit orchards were a common sight and

earned extra revenue.

In time, after the land was

continuously cultivated and cropped, weeds began to

appear. Crops were then rotated from field to field and summer fallowing was practiced, in the hope

that cultivating the empty plot at

regular intervals during the hot summer sun would kill the weeds. Orchard spray was the first chemical used for

pest control but in this present day

there is no end to the insecticides and herbicides available on the market.

During the early years no mixed

crops were grown as barley was considered too

heavy a feed for the horses. Wheat, oats and barley

were planted separately. Barley produced a plant

with a weak straw and because it was

unable to hold the weight of the grain, farmers began to plant oats with the barley, thus mixed crops. As long as a farmer still had horses, a field of oats was planted as well for their feed.

Today most farmers in the Formosa

vicinity plant mixed grain, and as well, corn is a very

popular feed for livestock and cash cropping.

HARVESTING Apples

Due to the fact that by 1900 most

of the farm lands had been cleared of timber there

developed an overseas market for apples. Nearly every homestead planted an orchard of several acres

and in a few years a cash crop from the

fruit trees added substantially to the farm cash income.

A domestic market for cherries,

plums and pears prompted every landowner to plant a

number of these trees to supply the family with delicious home-made jams while the apple trees supplied

apple jack and butter.

Barrel and stave mills did a booming business

and the need and method for spraying

the blossoms and trees to avoid insect damage was discovered.

Apple Clubs of thirty to forty

members sprung up in every area. Horse-drawn spray

machines were purchased and could move from farm to farm several times during the growing season.

The chugging of the hit-and-miss gasoline-powered spray pumps and the sight of

the men handling the nozzles from their

enclosed tower on the machine was very intriguing,

especially to children. Occasionally this operation was suddenly thrown into serious turmoil when bee swarms

were encountered.

In the fall of the year the apples

would be handpicked and piled deep in sheds. A crew of several men would come, sort and pack the apples, stencil the barrels with the different varieties and grades, and the Formosa's Fruit Growers Association was stamped

on each lid. These large containers

were then loaded on horse-drawn wagons and shipped by rail to Montreal where they boarded the freighters

for oversea markets. This rather profitable venture continued for many years,

but due to a failing overseas

market and succeeding frost damage killing the trees, it gradually faded out.

The apples which were rejected by

the graders, found themselves stored in the

cool cellars to be used for domestic purposes such as apple sauce, and delicious pies. Let us not forget

that mother also required a cash flow for

extra goodies, so most every evening during the fall and winter a pail or two of apples had to be

peeled, quartered and put into the racks placed

high over the kitchen stove. When sufficiently dried to a leathery texture they were packed into clean

white cotton bags. The whole family

assisted in the chore or preparing the apples. The local store would buy the apples or mother would barter them for

needed supplies. From the store they were

transshipped just as was done with butter, feathers, lard, soaps, wool and a

host of other commodities.

The crude methods of harvesting all

crops, used by the early pioneers have changed

drastically over the last one hundred years.

Haying

The earliest method of providing

hay consisted of the scythe being swung by hand and laying the green grasses

into windrows for drying by the sun and

air. As soon as it was wilted or partially dry the hay was forked into piles called coils. The art in

this process was being able to place the hay

in such a way that in the event of rain the umbrella shaped coil would turn the

moisture so that only the outer surface would bleach. After about a week of drying and curing, the

hay was loaded by fork into a wagon and

drawn to the barn to be stored for winter feeding. This method of coiling hay was used for many years.

The grass mower with a five to

six-foot cut bar drawn by one horse with shafts or

drawn by a team of horses had appeared by 1890 and served well for nearly a half century. Dump

rakes as well as the drum type side rakes

were used to roll the hay into swaths.

You

could bale up to 16 tons of hay a day with this 1913 International hay press.

But even

with the six-horsepower engine to squeeze the hay into

bales,

it still

took four or five men to operate it, and load hay into it from a

stack.

For a few years there was

a hay press in the community but even with the six horsepower engine to squeeze the hay into bales, it still

took four or five men to operate it and load hay

into it from a stack. The bales were

tied by hand with wire. In the late 1940's and early 1950's balers that tied with twine were being used in this

area.

Today haying is still one

of the farm operations that require extra men to help but with the bale-throwing balers which toss the hay bale

into a racked wagon, only one man is required in

the field.

Grain

CUTTING

At first the cradle was used by hand to cut

the grain. In the late 1860's the

horse-drawn reaper was a great invention. It cut the grain and raked it into neat bundles, but four or

five men were needed to bind the grain into sheaves. Women often helped in this back-breaking work.

The

McCormick "Advance" reaper was the last word in harvesting

at the

time of Confederation. It cut the grain and raked it into

neat

bundles. But four or five men were needed to bind the grain

into

sheaves.

In 1880, Massey Harris shipped eight binders to the area

from Brantford. Four were kept in Carrick with Ignatius

Kieffer, grandfather of John, owning one. These binders

were horse drawn and meant no more tying by hand into

sheaves.

This 1913 binder, as

its name implied, bound the cut grain into sheaves,

a big

advance over the reaper that left bundles to be bound by hand.

"Deering" was one of several names

within the International Harvester

family of farm equipment.

With the introduction of the tractor in the 1920's, horse-drawn binders very gradually began to fade away. Farmers Dominic and Herbert Borho jointly owned one of the first tractors. It

was an early fordson with steel rimmed and spoked wheels, which they purchased in 1922. Dominic did much custom work for the neighbours because of

this modern piece of machinery. The first rubber-tired tractor in

the Formosa District was owned by Ed Waechter. With this International

Farmal F-20, which he purchased in 1937, Mr. Waechter did a great deal of custom work. It ran on

gasoline or kerosene and today is owned by Andy Kuntz Jr. and is still

in use.

After the tractor-drawn binders, the swather was born. This machine cut the grain and layed it in rows on top of

the stubble. Gradually stooking became less popular and the local

farmers would bail thresh their grain.

THRESHING

Before the invention of the modern threshing machines in the early decades of the twentieth century, farmers would lay sheaves of grain out

on the barn floor, then with a flail would beat the sheaves until the grain fell out_ The straw was gathered and the grain being placed on a blanket

would

be tossed in the air to allow the wind to blow away the chaff thus cleaning the grain.

As farmers grew more grain, they were most

thankful for the horsepower machine and the threshing machine.

Before the introduction of the tractor,

harvesting needed very little fuel as most was

produced on the farm — grain for the

horses and wood for running the steam engines.

The horse was used to provide power by being

hitched to a very simple machine called

a horsepower which was an apparatus with two sets of cogs running against each other, attached

to and thus turning a long heavy shaft, which was connected to a pulley, from

which a belt was run to operate a

threshing machine. The most popular size was a four or five team unit. That is; the horsepower machine was

attached to a sturdy frame circle with pieces of wood, spokes or arms as they were called, extending thus allowing a team of horses to be

hitched to each arm. Each team was

tied to the team in front of them and the horses walked continuously in a circle, thereby turning the

horsepower machine.

With the power now there, the

first thresher consisted of a mechanism

called a cylinder and a few shaker decks, which threshed the grain and chaff from the straw. The grain

containing the chaff was then run

through a fanning mill to be cleaned while the straw was elevated to the mow or

on a stack in the barn yard. Joseph Meyer, father of Edmund, for many years operated a steam-powered thresher. His first steam engine had no traction, therefore required horses to move

it and the grain separator from farm to farm. Barn threshing often

lasted from August to December. Alphonse Zettel

purchased one of the first gas tractor custom threshing

machines in the area from C.J. Koenig in Mildmay.

Locally, Lion threshing machines were

manufactured in a foundry in Mildmay owned by Hergott Bros. and later by Lobsinger Bros. until just a few years ago. The threshing

machines were soon modernized with self-feeders

and straw blowers, and grain elevators and straw cutters became common

equipment.

Tractor-drawn combines came in before the

second world war and in the post-war

period, self-propelled combines heralded a new age of fast efficient harvesting.

Today, although a few farmers still use the

threshing machine, most of the Carrick, Culross,

Greenock and Brant farmers have their grain combined. About thirty-five or forty acres of mixed grain can be combined

in a day, truly a great change from the early years.

SOCIALS

At the close of the maple syrup season taffy

parties were often held. These were social

events, sometimes held in the bush but more often in the house, when friends and neighbours

were invited to spend an evening of fun and partake of as much taffy as they could eat. Taffy was made by boiling the syrup longer and then pouring it

over clean snow salvaged from some unmelted

snowbank.

Maple sugar was made by boiling

the syrup still longer, beating it vigorously and

pouring it into buttered flat-bottomed pans. No one ever seemed to get ill from eating maple products. Fond memories of these taffy parties are enjoyed by many old timers as they reminisce about the

good old days.

THE GOLD MEDAL FARM

About the time

of Confederation -1867- there came to this area a farmer with a great desire and ambition to succeed and excel, namely one

Andrew Waechter, born at New Germany, Waterloo County on January 25, 1845. Soon after purchasing Lots 1, 2, and 3, Concession A, Brant Township,

a two-hundred-and-fifty-acre plot, he set his sights to make it into a show place. He chose a high knoll as the setting or location for his

home and farm buildings. The earliest name for his

holding being that of 'Fairview Farms.'

Mr. Waechter soon employed a number

of men to clear the land of its vast amount

of hard woods. Trees were felled, logs piled high and brush set afire. The land contained a large amount of stones and therefore the

road fences were built of stone neatly piled six feet wide and three feet

high. Cedar posts were placed in a straight line to which barbed wires were attached. He had a fine feeding and water system, kept his land clean by rotating crops and produced high quality beef steers.

A contest was started and an 'Award of Merit',

which was called the Gold Medal Farm, was awarded to the winner. Andrew

Waechter's farm being in such excellent condition was the recipient

of the 1889 Gold Medal Award.

POWER

Oxen were

first used for power by the pioneer, until the land was cleared and then horses became the main source of power. The horse was used to pull the plow, haul the wood and timber to market, provide transportation on the mud and gravel trails as well as the wintery snow

drifted roads.

The horse was

used to operate the horsepower machine as previously explained under harvesting. Small power units called treadmills

requiring only one or two horses to operate it, were

used for light work such as pulping roots and pumping water.

When the heavy

timber frame barns were erected on the massive stone

foundation, these barns were considered sturdy enough to support windmills. Farmers were interested in cheaper power and thus windmills were used mostly for grinding grain for the livestock and pumping water.

In the 1920's

tractors were introduced to the area taking over much of the work of the horses.

Delco power came into

existence about 1925. Edmund Meyer did most of the wiring for the few farmers in this district that installed

this low voltage hydro system that made power from

a gas-powered generator and

rechargeable batteries. It was used to pulp turnips, run the washing machine and iron and

give light. With the advent of Delco power coal oil lamps were less frequently used.

The first hydro line was

brought into Formosa in 1915. Some 30 years later practically all farms were hydro equipped.

DRAINAGE OF LANDS

In the early years of

clearing the lands, it was evident that drainage was required to drain waters produced by winter snow and springy land, thus also avoiding soil erosion.

The first drains were made

by shoveling out soil, gathering millions of flat stones and laying them in such a fashion that openings were created forming a tunnel wherein water was

carried to a proper open outlet. Many

of these drains, one hundred years and older are still operative today. Had they been laid at a much

greater depth thereby not being

disturbed by deep soil machinery they would still be the most durable drainage material ever used. The care

and workmanship in their construction

has never since been equaled.

The use of sawn wood

planks to form tillage was then employed, especially when trees were plentiful and flat stones were scarce.

Next came the use of burnt

clay tile, with a flat outside surface for easier laying and non-shifting. The diameter of the tile ranged from two

to sixteen inches.

Concrete tile came about

with the introduction of portland cement which was commonly used in this area about the

turn of the century.

With the advent of

plastic, tiles constructed of this material became popular. Although plastic tiles are easier to

install, many farmers consider clay tile

to be a more durable way of constructing land drainage.

At first tile was

installed by means of a pick and shovel but now huge self-propelled ditching machines handle the

operations of digging and laying the clay

or plastic tiles, with the assistance of a few men to strike the levels and operate the machinery.

Back to Table of Contents

Forward to Chapter 8